Shyly Placed

On Final Fantasy VIII

For all intents and purposes, despite how this unfolds, this Review is a First Reading.

The place: time. The time: the proto-mid-prenatal internet days (The Wild West), 56k modems, when online shopping was starting to emerge. I put two video games into my cart on some dubious “Mom and Pop” angelfire/geocities hybrid-like website, the name I have no way of remembering. They were Chrono Cross and Final Fantasy VIII, both for the Sony Playstation, at eight bucks (?) a turkey. Weeks later a parcel arrived. Chrono Cross was inside, but no Final Fantasy 8. Disappointing at first, but it was quickly forgotten. I was so swept away by Chrono Cross it didn’t even bother me that I’d thrown away what little money I had then, and I eventually forgot about it. FF8 continued to elude my attention until the age of emulation.

In the past, attempts to play the game all-the-way progressed to a variety of conclusions and under much different mental positions. Bad timing. I have had some start-restarts several times, across several years, and due to the demise of several devices that were used to actually play the game— a laptop and console among them, had prevented a full cycle of the game’s story. This, today, this year, now, is the only completion so far, all wrapped by January earlier this year, played through on my Twitch Stream every Friday. Overall, it has reinforced some collected thoughts across age, diverged from some others.

Final Fantasy VIII, the predecessor to IX and so on, also reflected upon at this site, was released in 1999. Square Enix/Squeenix/S-kweh-nix (nee Squaresoft) had a surprise hit in Final Fantasy VII to an unprecedented, worldwide level. A veritable culture bomb, and a piece of the puzzle in the advent of the Cyberpunk genre. FF7 is one that has since experienced sequels, side-stories, movies, and a couple of proper, re-interpretive remakes to capitalize, in FF7: Intergrade and the recent FF7: Rebirth. Like FF9, as far as Playstation-era Final Fantasys go, FF8 hasn’t had anything of the sort. Unlike FF9 though, FF8 has much less rapport from series fans since its initial release, to put it lightly, or at least my understanding is that it is generally despised in the series fanbase. Despite its then and now merely lingering popularity it has a cult-like, “underground” reputation, even though upon release it was a commercial megahit.

Much of this, I imagine, could be accredited to something like Sophomore Blues, the subjective failure to meet expectations in the follow-up after a hit debut, usually suffered in discographies. Blame is probably more appropriately placed in its eccentricities in plot, characters, script, and mechanics, which are studded with baffling design choices. While all these are instrumental in FF8’s kind of inaccessibility, it offers a profound voice in its place. This voice has reminded me of other off-center, leftfield game auteur/producers like Goichi Suda (Suda51) and Hidetaka Suehrio (Swery65).

“If you’re recommending me a game series, point me toward ‘The Final Fantasy VIII’ of that series first.”

The above I recall someone saying on social media, vaguely sourced to all the way back circa 2008. If recalling it now wasn’t enough proof-of-purchase in this line of thinking, well, I’ll redouble that it would be lying if I said this didn’t inform how I felt about FF8, not having reapproached it yet. But why? What does that mean about FF8? For a long time, since I became a fan, and since that sort-of axiom, I’ve sat through daydreams on the series. It is a thought schematic that has provided a scope with which to view other franchise games, colored my reflections. With that said, what does that mean? What is Final Fantasy 8? What’s it all about, and what are those things that divide fans? Why is it special to fans?

Final Fantasy 8 follows Squall Leonhart. Squall is a teenaged “Gunblade Specialist”, at a facility called Garden, a futuristic military school that “cultivates” SeeDs (some even from birth, it can be assumed), which are elite mercenary forces. SeeDs are trained in a number of different kinds of covert and specialized for-hire operations, but are essentially developed to defeat Sorceresses, a powerful, recurring threat to the World, or so we’re told. Sorceresses seemingly exist at no more than one at a time. The rest of Squall’s party throughout the game, save for two eventually, are made up of SeeDs. Side note: The planet in this game does not have a name, or at least I hadn’t found it combing the game’s information centers.

A core part of the game’s world are in Guardian Forces, or GFs as the game often uses them. GFs are summoning creatures, or essentially monsters revered as demi-gods invoked for power, magical beings that may or may not be endemic to the world; their relationship to humans or the sorceresses is never clear, but are nevertheless a reality. GFs are the main arsenal for SeeDs, the defining feature in what separates them from your average person. SeeDs form contracts with GFs, and it’s later revealed that these contracts come at a price: the SeeD’s memory. GFs, though having much in relation to Final Fantasy VI’s Esper system, are tweaked so much here to serve as the beginning of the end for the game’s mechanics...

One thing I’ve enjoyed about this game, toe-to-toe within its series, is the number of things mechanically that crochet through the game’s world. Many of these items are introduced, but are effectively hidden; only in the effort of investigation are the details made apparent, and I think the additional understanding rewards somewhat.

For one, from looking at a character’s stat page, in comparison to most human enemy soldiers (one has to use a Scan spell to see these, or online sources), SeeDs have lower base stats. This is logical, because a teenager, even a trained one, generally wouldn’t outclass an adult soldier. Using GFs are what makes SeeDs special. Using a GF requires you to combine them with characters, in an action called “Junctioning”, which boosts abilities. GFs effectively replace equipment, like weapons and armor, though the former has its own upgrade system in place.

There is Magic in the game’s world, but it is explained in the lore that only Sorceresses can naturally wield it. Alternatively, scientists have developed a form of para-magic the characters can use. It is even implied Magic is such that even regular Joes can sport it, with enough training. SeeDs on the other hand, form contracts with the GFs in order to cast magic easily. The aforementioned memory loss from GFs is an integral part of a plot twist in the game, but has no effect in everyday combat.

Spells available to the player come in the form of consumable items, and are permanently removed when used. Spells can be equipped to specific stats or elemental/status defenses after junctioning with a GF. Equipping one spell to a stat adds practically nothing, so it is necessary to stockpile and compound more of that same spell to be effective. As a caveat, actually using these spells, if junctioned to a stat, reduces those stats they are junctioned to, so it is necessary to retain that stock of spells. This has an odd overall priority re-emphasis. Whereas most Final Fantasys, and broadly all RPGs, have Mages as core components of player parties, in FF8 it is more of an advantage to NOT cast spells, channeling energies to augmenting base stats rather than magical power. Though it is still to a player’s advantage to cast certain spells, it is more situational, or more of a condiment. This spellcasting role seems to have been delegated more closely to summoning the GFs, which cast a free ability when invoked mid-battle after a timer finishes. During this timer, a GFs separate Hit Points stat temporarily covers the character summoning them, which has further situational strategic value.

A convention in JRPGs is the acquisition of money through defeating enemies. This system is replaced in FF8 entirely. Instead, players earn money through automatic compensation via a “salary” system, where at regular intervals they are given a “paycheck”. How much a player earns is dependent on another factor, SeeD Rank, which ranges from 1-30. SeeD rank decreases over time and is dependent on a number of things the player does. Some of these activities have to do with portions of the game’s story (such as conduct when on a job), but for the most part can be increased through battling enemies or completing in-game trivia, called a “Written Test”.

Furthermore, the game has an odd character leveling system when compared to the rest of the series, and the genre itself. Typically in RPGs, gaining levels means the characters effectiveness in battle is generally improved. In FF8 however, leveling characters itself offers little in the way of stat bonuses. Enemies also globally scale to the characters’ average levels, gaining those stats contrary to the player, becoming stronger, and can affect item drops after battles. Blindly leveling characters without utilizing the Junction system can trap the player. On the other hand, utilizing Junctions hand-in-hand with this scaling is an advantage for players who favor a low-level playthrough of the game, which can be manipulated easily with a certain GF ability.

When I was a teen, this was all fairly confusing. To some degree it still is. Out of the box, it is unconventional, and not much in the game explains how to take advantage of such a setup other than basic, brief tutorials when introduced. In effect it acted as a boundary against accessibility. By now hordes of dedicated players have found ways to exploit this system, often developing characters that are end-game viable almost immediately after leaving the first area, Balamb Garden.

If I’ve spent too much time sounding like a Wikipedia, it’s to demonstrate to those that don’t know just how strange this game is before one even gets started with the story. The Junction and GF system is perhaps the most interesting thing in the whole series, I feel like if this system had some refinement it could be intoxicating to customization-thirsty players. To this day this hasn’t been realized.

It’s a really bold experiment from the comparably tame Materia system in FF7, and even FF9’s Weapon/AP learning system is rendered dull. Like those games, there are configurations that are more optimal, but in FF8 there are more ways than ever before to create specific parties whereas before and even after, characters are guard-railed into certain roles. Min-Maxing is a different story, but the capability is there.

The top minigame in FF8 is a card game, the building blocks to FF9’s Tetra Master, the infamous Triple Triad. On its own, it’s fun, has great theme music, and many NPCs in the game play it, so there’s plenty of opportunities for games and more cards. More than that though, it is one of the keys to rendering the game’s difficulty inconsequential. Through GF abilities, the character has the ability to turn cards into items or powerful spells, through “refinement”. Spells made through refinement can be junctioned to the character immediately, the only cost being time spent playing opponents.

My distaste for Triple Triad though, is almost wholly in the domain of Card Rules, which shift regionally within the game’s world. Though that alone isn’t altogether a “problem”, but is further complicated by being able to pass these rules to other regions like a virus. From a design angle one could conclude this is a way of increasing difficulty as you progress through the game. To that end, and to my frustration, it is very easy to acquire and likewise pass-on undesirable rules or variables that can make winning games practically impossible. For me anyway, I had very little control or inkling as to how this system worked, and at times felt arbitrary. Having said that, this isn’t too far from what players despised from Tetra Master.

My first few times playing, the capability of turning cards into items eluded me, like many of the game’s options. Much of the game to my young mind, one that put up a good fight to learning the game’s speed and rather beating my own drum, led to my general write-off at one point. Through design, the player is most likely to intuit primarily one must “draw” spells from enemies during combat to acquire them. This method can be time consuming; refining spells is much less investment.

That about does it for mini-games though. The rest are hodgepodge, typically encountered through the game’s narrative, or are otherwise walled-off into obscurity like many of its side-quests. Like those side-quests as well, they tend to not yield very many boons or bonuses due to many of the same ends being just as easily acquired through other, more organic means, so there’s little impetus to seek them out.

With that in mind, this playthrough at least shook up how I pre-emptively felt about the series, even though at this point its reputation is one of reinvention each new mainline entry. One has to consider what a burden it must be to the developers, pressured to redesign each new game from the ground up, whereas perennial rival Dragon Quest have remained mostly static with its design schemes, one of its qualities cherished by fans, myself included. On the other hand, it’s a freedom to try new things, and it is exciting to see what the developers come up with for each new game. The expectations now though, are so much that if what is eventually devised isn’t something that, first and foremost, works, and secondly the more etherial, “fresh”, it tends to disappoint most players. To most people I think the former shadows the other.

Visually, FF8 was top of the line. Full Motion Video comes back in a more robust manifestation, and greater volume, in all manner of extraordinary situations. The famous waltz scene, utilizing motion capture, then fairly new to games in general, is still pretty great. To me, the best of these are in (a quick spoiler) outer space. There’s also something about certain Playstation games that’s really special to me, one of failproof zest; that moment when an FMV transitions to the real-time graphic look in a scene. Some of the most impressive ones on display in FF8 are when the two mesh, one of these is during a large, high-flying battle between Balamb Garden and Galbadia Garden. It’s hard to tell if it’s easy to replicate, it seems confined to the era, and nobody since has attempted for the same effect. Or at least, any I’ve seen.

Another way that this game still looks impressive is its expansion of character modeled body language. Rinoa has the most of it I think, or at least the most where I took notice, while Zell is in second place, but it isn’t limited to them. There is no shortage of exchanges between characters using body language that really flesh out those characters in various ways. Even my first playthrough I noted, in an early scene, a conscious control over the character models and the timing in their speech. I’m speaking of the scene at “make-out hill” with Squall and Quistis in the Training Area, to those keen. “Go talk to a wall.”

For the record, character body language has been around even back to gaming’s 16-bit days. Characters have been modeled to emote using gestures and facial restructures to express states and moods for much longer than we tend to think, if at all, about its progress. What makes FF8 so special at this is that, for the time, it was state-of-the-art, and as far as I can tell, making the most of it. Sometimes this gives it what I hesitate to call poetry, or the effect of something between the pages.

The proof is inside the pudding— all one has to do is compare 7 to 8— character models have much more real estate to position themselves in the form of more joints and articulations to explore these choreographies. It’s one thing to be able to do these things, and another to use these things with a creative direction. The result(s) of these is mostly charm-based, as they reveal personality through gesticulations, simultaneous however, there are several scenes that carry unprecedented nuance in this body-acting alone, at least in the series. The vocabulary of pantomime was expanding. This would continue to incline in FF9 and so forth, especially when Final Fantasy X took it “where nobody had gone before”.

Among its many firsts in the series, FF8 is a narrative that chiefly orbits something that most feel synonymous with the series now: a Love Story. Whether it is touching or not is up to you, for my part though, I would consider it effective. Both the bonafide introduction of this thread and its subsequent fulfillment occurs much later in the game, the latter after some of its most intense dramatic strokes, and not with particularly much pomp as “out of this world” it is, so this game’s story isn’t particularly about it while it remains central. Rather, much of its focus is about the journey there, principally in one half of it, as most of the game is about Squall, and later Rinoa’s possession episode, but these two eventually collide in operatic fashion.

I should note one of FF8’s strange narrative choices before going any further. At several points in the game, an unseen force places the player’s three active party members unconscious, sometimes in potentially dangerous situations. In each of these episodes, they are transported to past scenarios inhabiting three additional characters the player then controls, who are soldiers in service of the region of Galbadia: Kiros, Ward, and Laguna. Strangely, Squall’s active party seem aware in these visions and sometimes comment on these scenes as they are happening. The situations they encounter vary from funny Romantic escapades, solemn slice-of-life memories, to military operations. Even further, there are items in the game a player can examine that affect these memories, slightly altering them. It is a more engaging way of showing a “B-Side” to the story, providing more context than just a simple flashback, and character moments in the past that have relevance to character details in the future. Some of these precipitate in characters having inside information about places they visit in the Laguna episodes later in the main story, such as a techno-oubliette compound that they must escape.

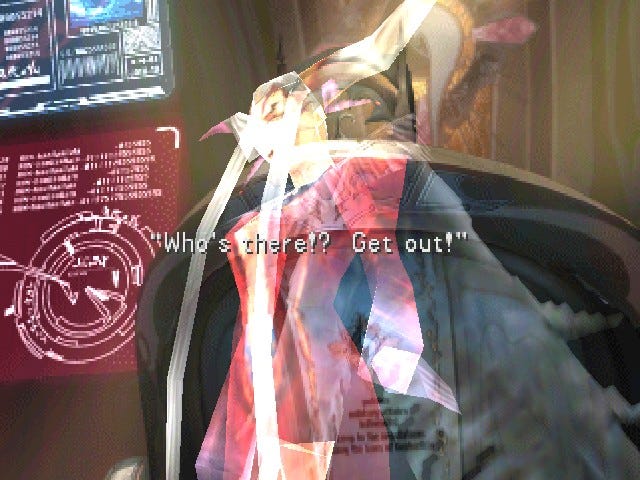

One of these Laguna-informed details I’d like to magnify briefly concerns Seifer, who I’ve not mentioned yet. Seifer is a prospective SeeD, and the second gunblade specialist of Balamb Garden. Superficially, he is Squall’s rival, in both Garden hierarchy and later in love, but in his own right comes to grasp a Villainous role, like the Sorceresses. What this has to do with Laguna and his crew is one of those Obvious Subtlety type of clues. Or in other words, it’s on the screen, but can easily be missed or not thought about.

In every encounter with Seifer, as a party member or enemy, he takes this stance as he idles in combat, holding the gunblade stylishly side-arm like a gangster. Not that this posturing is different from the way a fencer might hold his epee, but I was thinking primarily of the “gun” part of gunblade.

Anyway, at first this indicates his deviant nature compared to Squall— he’s narcissistic, acts like a punk, has no loyalty to authority and, in no small article, male authority, made clear when he subjects himself as a Sorceress’ Knight to Sorceress Edea, the initial, primary villain. Beneath the surface though, there is another reason.

In one of the Laguna flashbacks, and said in several pieces of Lore the Squall party can find, Laguna needed money and acted in movies (yes they have those too, as well as a movie industry) to that end. One of these was a sword-and-board fantasy movie, and in one of the flashbacks a scene being filmed is a fight with a dragon:

Laguna holds it in the same way. With that evidence, and the constant supply of Seifer’s threads in a Romantic Dream, you can conclude that Seifer himself saw this movie as a child, loved it, and modeled his inner life around it, projecting it onto the world, and more literally adopted the same stance, unwieldly as it might be. The fact that this item is never brought up, save for through NPC dialogue and cryptic things Seifer says, allows the player to piece it together.

Additionally, you can tell that Seifer truly believes in those things, and his “evil” is not really just that. He’s still a teenager after all, and sees the world through a childhood fantasy, similarly to how Squall sets up his worldview through an abandonment complex. Seifer leaves the party early and for most of the game, but his journey is still a parallel. This parallel comes to a head when Squall himself assumes Knighthood bound to a Sorceress, and the true meaning of being a Knight is explained.

So at that, let’s talk about Squall. Most of the game is through his eyes and his inner monologues, and I stress the latter because it provides a considerable chunk of the player’s understanding of him. After the game’s overture, much of our introduction to Squall is that of what we think children programmed by military school would be, cold and business-like, but also naive to the feelings of others. He can’t read a room. Still, he is proven competent in his role, not without struggle of course, when he, like most JRPG protagonists, ends up with a crew of motley, idiosyncratic dopes.

Revisiting this now, it was astonishing just how much dickery Squall whips the others, whether by dismissal, neglect, or pointed insults. He resents everything: his position, everyone’s support of him, people Liking him, forcing him into leadership, or any manner of situations where others rely on him. For much of the game he has an Arm’s Length With Industrial Strength attitude towards relationships, and it’s a fight not easily won. This is a prelude that lasts for a long time. In small doses, but in no small way, there are moments where Squall comes through for the party under duress. One can see early, during an assassination attempt on Sorceress Edea, in spite of his sourpuss, he comes through with emotional support for the principal sharpshooter. It’s these ephemeral moments that provide pleasurable closure and a display to see Squall’s incremental growths from a doughy obstinance to a honed, charismatic leading man. A learning man, despite all his struggling against his fate.

The Sorceresses (Edea, Adel, Ultimecia, Rinoa) and their participation in Final Fantasy VIII is also of great interest. Considering the series, the Sorceresses mark the first overarching villains that are overtly Matriarchal, or more plainly, female. Sorceresses as enemy in the general folkloric past, across all of them, are often one dimensional. They are evil for evil’s sake. In the game, everyone, even the player, is trained to think they are malice incarnate, and are harbingers of the End. In FF8, the Sorceresses have a lot of influence, but most people haven’t even seen one. As the party persists in apprehending Sorceresses, it becomes clear that they are misunderstood. Many times the Sorceresses ask in desperate notes why they are being hunted down by SeeD in the first place. SeeDs have essentially no clue either, restricted to “the way of things”. Evil must be vanquished, the stereotype in all that is Heroes of Might and Magic.

This confusion is nucleus of the story. The Sorceressphobia is fed through misunderstanding and fear, so both opt to decisively erase the other believing this will restore order. Throughout the game, the struggle to understand the Sorceresses is explained through Edea, one who was possessed by a Sorceress and later freed, that a Sorceress requires a Knight, a not necessarily Romantic relationship. This coupling is symbiotic, the Sorceress is a caretaker of power and secrets, but unstable, tempted by evil, and this is retained by her Knight. The Knight, a male role, is the Sorceress’ security, conscience, and keeps her in check. We’re led to assume that, somewhere down the line, a Sorceress was neglected, betrayed, or otherwise failed by a Knight, spiraling into the events of the game.

To say this playthrough has qualified FF8 to the top hierarchy in my mind could be understatement. This required some effort and time on my part, and it’s better late than never. Like anything, it’s what you bring to it. Its yield is greater than that, I think, and I wish my mind was better situated to its constrictions, and its liberations when I was younger, and that I took a stand when it blew my cash on it that first time. Whether it consummates with the quote at the start of this post, I’m not sure, but if anything I see what they’re saying. In some ways this ages better than the other two PSone entries, due to that sentiment, and for now, I’ll be waiting on something to come along that takes its experiments and explores them further.

I’ve subtracted many things I would have liked to include, such as other Character profiles, but it’s time to tie a bow on this entry. I want to pay brief dedication to how funny this game is. It is filled with game-specific situations, and things characters or NPCs say, that are classic for good reason. Most of them don’t translate very well in just pictures, so these are of course excluded. You’ll have to play it yourself, or play it again. This collection will hopefully convey that. Some of these are already included above, here’s more, with as many of the iconic ones I could find:

P.S.S.— during the final stream of the game, a friend made a “Versus” “AMV” video of the game’s trippy conclusion. It is perfect. Spoilers, obviously.